Download the PDF

A few weeks after the European elections, after seeming deadlocked for twenty years of negotiations, the trade agreement between the European Union and the four countries making up Mercosur (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay) is going to be signed. If the details of the agreement have not been made public, the Commission’s communication documents already give elements that will be put forward to obtain the ratification of the agreement by the Council and the European Parliament and, but it is far from certain, by national parliaments.

Meats and sugar on the front lines

On the agricultural side, the beef and poultry sectors and the sugar and ethanol sector are particularly concerned by European concessions. Even though there is widespread recognition of the environmental services that herbivorous farming provides in terms of storing carbon in pasture and maintaining landscapes, farmers can hardly understand the value of opening up a little more a European market already affected by reduced consumption of red meat. And this is all the less acceptable as cattle farms are the ones with the lowest incomes despite significant public support, in particular coupled support for suckler cows, which is more than ever under the threat of a 15% decline in the budget of the CAP.

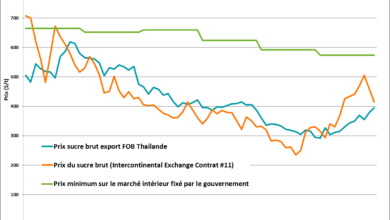

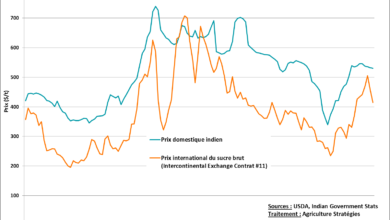

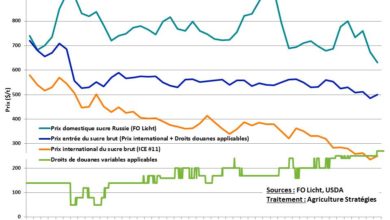

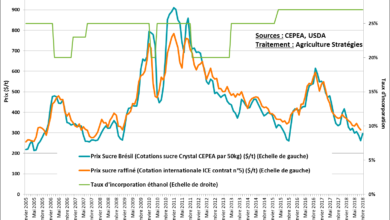

The sugar sector is also in crisis since the end of quotas in 2017, which has led the EU to become the only producer country directly linked with the export price of Brazil, the most competitive country in this area. As for the EU-Mercosur agreement, the Commission had promised to take all the measures within its reach to avoid the crisis … but nothing has come and the preliminary versions of the report of the “Task Force” provided for this purpose indicate that nothing will come from it. The same can be said from the point of view of the ethanol sector, closely linked to sugar production, which is just getting its head out of the water after the Commission has had to go back on its goal of halving the mandates of incorporation, the main tool for developing this renewable energy sector.

While multilateralism is in crisis, that Donald Trump is only saying out loud what the Americans were already doing – “America first” – that all countries are strengthening their agricultural and food policies not out of protectionism but only because their food safety is not compatible with direct exposure to international dumping prices, why does the Commission persist? The current CAP is already hanging over a thread since the Americans have challenged its flagship principle, the decoupling of aid, but the outgoing Commissioner has not even begun to anticipate a shift in his reform proposal, that he never succeeded to bring to its conclusion.

Why now ?

In addition, why offer new tariff quotas even though there is great uncertainty about the distribution of current quotas in case of hard Brexit? It should also be noted that, strangely enough, the British, after explaining to us the benefits of free trade, are not fighting to recover these preferential accesses!

This dark depiction of the situation is not offset by the possibility of exporting more cheeses and milk powder for farmers who suffer, without benefitting from it in anyway, from the desire to expand the European dairy industry and who have no insurance, unlike their American counterparts, to benefit from a fair sharing of value and countervailing measures in the event of a price drop.

So a question arises: why now? Some highlight the interests of the German automotive industry, but don’t all manufacturers already have factories to produce locally? Is it, on the contrary, the observation that European opinion, and the debates of the European elections have shown, is less and less fooled by the fable of happy globalization, and that the outgoing Commission is undoubtedly the last to be able to make an agreement of this type?

The last globalist stand ?

This could all be likened to a last globalist stand from the European Commission, which does not seem to have other spokespersons in France than Pascal Lamy, the chief of certainties in the 1990s, seems all the more desperate. On the other side is a Brazilian President who refused to host COP 25, re-launched deforestation and re-authorized 239 molecules, most of which are banned in Europe. And the argument that this EU-Mercosur agreement is the way to force Brazil to meet its commitments in the Paris Agreement (reduce by 37% its emissions of greenhouse gases and reforest 12 million hectares in 2030) is even less convincing that nothing is planned in the event of a breach.

Because it will really become difficult to defend the European construction when after the coal and steel, the “communitarization” of the policies of a sector like that of agriculture, will become synonymous of its liquidation. Should we hope that we will witness the last episode of an endless rush of a European Commission which has sought to postpone until the last moment its politico-economic aggiornamento. The one that consists in no longer believing that the sole invisible hand of the market leads to the best of all worlds. Whoever seeks to be a source of proposal to build a new international order in agricultural matters where the objective is no longer to boost the competitiveness of its agri-food sector at all goes by institutionalizing the dumping of agricultural prices. The one who, in agricultural and food matters as elsewhere, is to think that public intervention remains justified in the name of the general interest, social justice, environmental sustainability and economic efficiency.

Jacques Carles, President of Agriculture Strategies

Frédéric Courleux, Director of studies for Agriculture Strategies