Download the PDF version

WTO compliance is one of the most frequently cited arguments to justify the CAP’s inertia and its obstinacy in using ineffective decoupled subsidies, which it remains alone to stand for. Yet, on the opposite Atlantic coast, our American competitors abandoned decoupled subsidies back in 2014, replacing them with support tied to market prices, even though these are considered market-distorting, without facing any retaliation. While the EU adheres strictly to WTO rules and has significantly reduced all forms of support—especially market-distorting support—over the past 20 years, the United States has taken the opposite route, quietly yet steadily strengthening its direct support in recent years.

Agricultural support measures must be reported to the WTO and are classified into three boxes: the green box, which includes supports that do not disrupt trade and therefore do not need to be reduced (including decoupled subsidies); the blue box, made up of direct subsidies with conditions to minimize influence on global prices (including production-linked but not price-linked supports); and the amber box, which contains direct supports that influence producers’ decisions and “distort” market signals (such as countercyclical supports, guaranteed prices, and crop insurance). The amber box is capped for developed countries.

Unlike the EU, which acts as a model student, the United States skillfully uses every available loophole to at least appear to fulfill its WTO commitments, all while managing to substantially reinforce its agricultural support.

Food assistance, central to the system, directly funds purchases from local producers

Food assistance, which annually represents about $100 billion and 75% of the Farm Bill budget, serves as a substantial indirect support for American farmers, significantly reinforced during the COVID period. Food stamps are credited to a card that can be used only in licensed stores restricted to strictly food-related purchases: fruits and vegetables, meat, poultry, fish, dairy, bread, pasta, and cereals. To qualify for a license, at least 50% of a store’s sales must come from food items eligible for food stamps, or it must offer at least three types of items from each of the four basic food groups (cereals and bread; fruits and vegetables; dairy products; and meat, poultry, and fish) daily; at least two of these categories must contain perishable foods. Food stamps are thus targeted towards fresh and unprocessed products, which in turn promotes the consumption of U.S.-produced goods.

But there’s more: farmers can also be paid through food stamps within short supply chains, meaning that food assistance also supports direct purchases from producers. Between 2013 and 2020, spending on food assistance in farmers’ markets nearly doubled, reaching $33 million annually. In 2020, an additional $2.5 billion was allocated through the “Farmers to Families Food Box” program, a direct purchase and redistribution initiative created during the pandemic. This amount supplemented $52.2 billion distributed in direct aid (countercyclical assistance, crisis aid, and crop insurance). Above all, food stamps are targeted toward fresh, unprocessed products, directly benefiting the U.S. economy. The latest study estimates that every $1 billion spent through the SNAP program (the primary income-conditional food assistance program that constitutes 60% of food assistance) generates an additional $32 million in agricultural income for farmers.

However, food assistance spending is not included in the support counted by the WTO. All food assistance, including the portion involving direct purchases from producers, is categorized in the green box, which is exempt from reduction commitments. This classification raised the green box amount to $139 billion for the 2020 fiscal year.

Calendar year or fiscal year?

The United States has developed an intricate method for reporting its agricultural supports to the WTO. Despite the extensive aid provided to the agricultural sector, they manage not to exceed the “amber box” ceiling of so-called trade-distorting subsidies, which amounts now approximately $19 billion for them. To achieve this, they heavily rely on the de minimis provision and skillfully manipulate reporting periods, spreading direct payments across fiscal years rather than aligning with calendar years.

While their total agricultural support for the 2020 calendar year reached $52.2 billion (including $6.5 billion allocated for crop insurance), their total notification to the WTO for 2020 was reported at only $34.5 billion, with just $18.2 billion counted within the amber box.

According to USDA data[1], the 2020 calendar year expenditure included $23.5 billion under “USDA pandemic assistance,” primarily through the CFAP (Coronavirus Food Assistance Program), consisting of direct crisis payments to producers. However, the USDA managed to report only $11.9 billion of this $23.5 billion to the WTO, by taking advantage of reporting periods: CFAP was split into two installments, one of $16 billion in May 2021 and another of $14 billion in September 2021. For the WTO, it is the U.S. fiscal year that matters, running from 10/01/2019 to 09/30/2020 (corresponding to fiscal year 2020). Payments made after October 1, 2020, will thus count toward fiscal year 2021. The advantage of dividing support based on reporting periods becomes clear.

De minimis aids to conceal spending

Additionally, CFAP aid was partially declared as product-specific support ($11.39 billion) and partially as non-product-specific support ($53 million) to allow the United States to maximize its leverage under the de minimis aid scheme.

| Encadré 1 : les aides de minimis The de minimis scheme is a tolerance mechanism under WTO rules: all direct support that represents less than 5% of a product’s value is counted as zero and is not included in the amber box. This rule applies both to product-specific support and non-product-specific support: if “non-product-specific” MGS (Market Gain Support) is less than 5% of the total product value of the country, it is also not counted. |

The United States carefully ensures that non-product-specific support does not exceed the 5% threshold, allowing these to be classified as de minimis aids, which are excluded from the amber box. For fiscal year 2020, this approach resulted in $13.2 billion being excluded from the amber box as non-product-specific support, while the EU declared less than €1 billion.

The $53 million from CFAP is therefore not accounted for, along with a portion of CFAP support ($1.3 billion) targeted at specific products, where the amounts did not exceed 5% of the production value of each product. In total, U.S. product-specific support under the 5% threshold amounts to over $3 billion, compared to €1.4 billion in Europe.

Thus, out of the $11.9 billion in CFAP payments notified for 2019/2020, only $10.1 billion is ultimately counted within the amber box. Thanks to the de minimis scheme, the $34.5 billion in direct aid reported by the United States to the WTO for fiscal year 2020 is ultimately reduced to $18.2 billion, just enough to remain under their permissible amber box cap of $19 billion. Almost impressive enough to inspire admiration…

Subtle Yet Tangible Increase in Direct Support in the US, in Contrast to European Trends

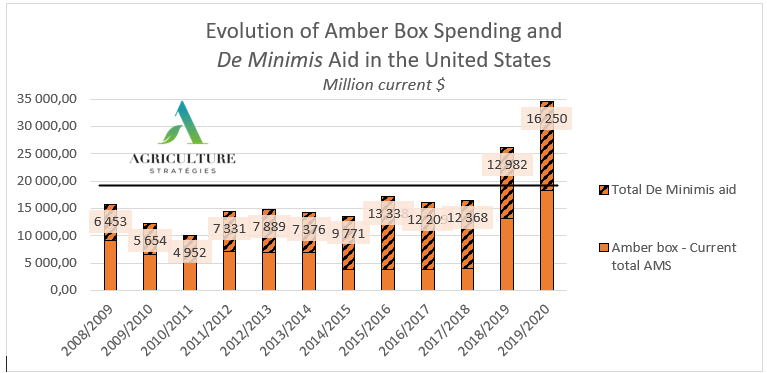

The use of de minimis aid appears to be a well-established practice among our neighbors across the Atlantic, as its amount has been steadily rising since 2015 (the year decoupled subsidies were abandoned), allowing them to consistently stay below the admissible $19 billion threshold, despite an increasing reliance on distorting aid… At least officially, since in reality, this threshold was exceeded in the 2018 and 2019 campaigns when de minimis aid is taken into account.

Figure 1: Evolution of Spending Classified in the Amber Box and De Minimis Aid in the United States, in Current Euros, Source: Agriculture Stratégies based on WTO Notifications

Figure 1: Evolution of Spending Classified in the Amber Box and De Minimis Aid in the United States, in Current Euros, Source: Agriculture Stratégies based on WTO Notifications

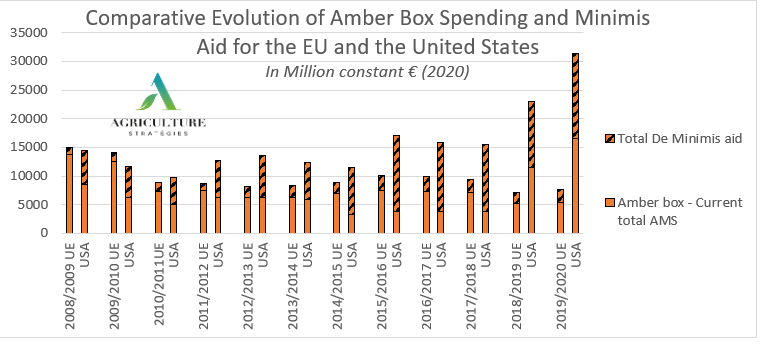

In comparison, the EU, which has a ceiling of €72.3 billion in the amber box, spent only €5.3 billion on support considered to be distorting in the 2019/2020 period, €68.5 billion in the green box, and €4.9 billion in the blue box, acting as a naive player compared to the Americans, without resorting to the same strategies. Between 2010 and 2018, this strategy even allowed the United States to officially report a lower level of amber box support than the EU, while in reality, including de minimis aid, their support was higher—something the United States is fully aware of[2]. When adjusted for constant euros, the shift in U.S. strategy and the difference in approach between the two powers becomes clearly visible from 2012 onwards.

Figure 2 : Comparative Evolution of Amber Box Spending and Minimis Aid in the United States and the European Union in Constant Euros (2020), source Agriculture Stratégies based on WTO notifications

Figure 2 : Comparative Evolution of Amber Box Spending and Minimis Aid in the United States and the European Union in Constant Euros (2020), source Agriculture Stratégies based on WTO notifications

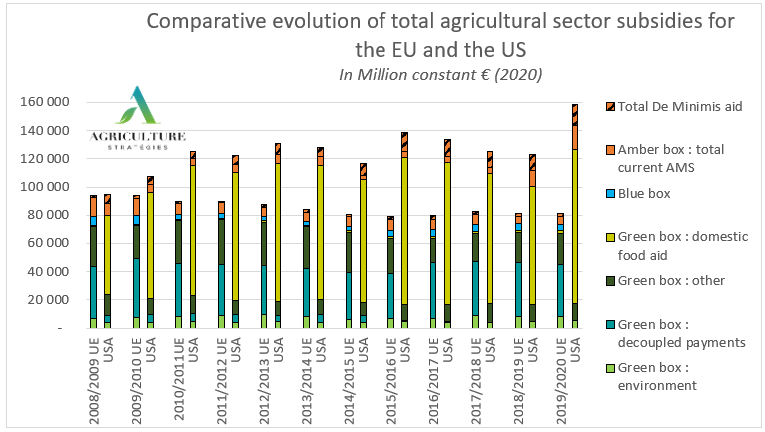

This shift in American policy has been visible since 2010, when all forms of sectoral aid, including food assistance, are included in the comparisons. While the EU has stabilized around a reduced level of support, the United States has significantly increased theirs and adjusts it according to needs.

Figure 3 : Comparative evolution of total agricultural sector subsidies for the United States and the European Union in constant euros (2020)

Figure 3 : Comparative evolution of total agricultural sector subsidies for the United States and the European Union in constant euros (2020)

Since 2010, the U.S. government has been providing more support to the agricultural sector than the European Union, whether in terms of distorting subsidies or overall aid, whether measured in constant euros or relative to the value of production.

With all due respect to WTO enthusiasts, it can be observed that while the amounts spent on farmers from 2019 to 2021 have indeed caught the attention of the United States’ trading partners, who raised questions during discussions at the WTO, they have not yet led to complaints, despite vague responses or even non-responses from the U.S[3]. While the United States does not hesitate to file complaints about agricultural support from other countries—after successfully challenging China’s guaranteed cereal prices in 2016, the U.S. also challenged European decoupled subsidies in 2018 within the framework of the Spanish table olives case, which was unsuccessful as the WTO ruled in favor of the EU.

Will the United States’ disregard for WTO rules eventually be sanctioned? As the new Farm Bill, which will come into effect from October 2023, is being drafted, U.S. notifications for the 2020/2021 period will likely be closely scrutinized and subjected to intense discussions at the WTO. It is certain that this time, the de minimis aid regime will not be enough to conceal the scale of the support granted to the agricultural sector, which will result in the U.S. failing to meet its commitments due to a significant breach of the amber box threshold[4]. What consequences will follow? Let us recall that the WTO’s functioning has been blocked since 2019 precisely because the U.S. refused to appoint new judges to arbitrate international disputes within the dispute settlement body. If this blatant violation of WTO rules goes unpunished, it could signal the end of international trade rules. How will a Europe, already weakened by energy challenges and potentially fragmented by divergent national stances on the conflict in Ukraine, react—especially given its pronounced tilt towards the protection granted by NATO… and thus the U.S.?

September 2022 28th

Alessandra Kirsch, CEO of Agriculture Stratégies

Translation by Valentin Gesquiere, Tour de plaine

[1] https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/farm-income-and-wealth-statistics/government-payments-by-program/

[2] See the Congress Report on the topic:

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46811/2

[3] https://agims-qna.wto.org/public/Pages/fr/ViewQnA_Validated.aspx?officialID=94039&caller=http://agims-qna.wto.org/public/Pages/fr/SearchResult.aspx

[4] https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46577