During an audition with the House of Lords on 8th March, George Eustice, British Minister for Agriculture, Fisheries and Food gave some guidance on the consequences of Brexit on UK agriculture1. If, at this stage, “we have not reached any decisions yet about exactly what the structure of a future UK framework might look like”, the Minister states “the golden opportunity with Brexit is the chance to do policy better”.

The new British agricultural policy he is calling for will be organized around “two plans”: one for the environment and one for food and farming. He freely criticizes the current orientation of agri-environment schemes, which he finds too centralised and too prescriptive, and in contrast, he advocates more coherent (holistic) approaches based more on local dynamics and challenges (groundwater or landscape).

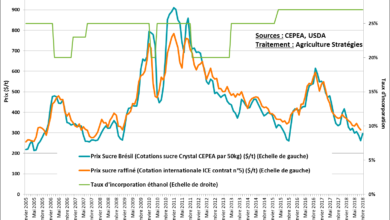

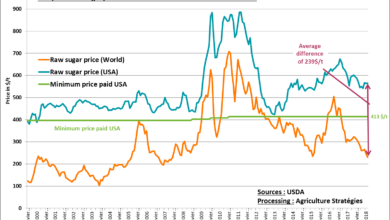

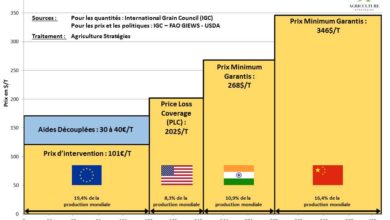

For farming, his approach is clearly pragmatic and based on what works in terms of support policy. Reminding us that this sector is “exposed to risks, such as weather, very high market volatility, animal disease outbreaks, all sorts of problems”, he uses the United States and Canada as an example for considering “government-backed insurance schemes or countercyclical disaster payments or incentives to help farmers set money aside for a rainy day”.

Obviously, he is not in favour of decoupled aid. For him, most of the subsidies disappear in increased, inflated rents and intermediate consumption but also through the undervaluation of farm produce. More categorically, he clearly states that he wants to move away from the logic of the level playing field which consists of justifying subsidies to its producers in compensation for the supports perceived by other producers. Agricultural policy should be a means of giving farmers “a competitive advantage in the world because we have good policies that support them to become profitable, competitive, productive and sustainable”.

The concrete translation of what could be considered an ideological break from free trade will consequently be objectified in the negotiation between the United Kingdom and the EU-27 on community sharing on distorting support measures, the WTO amber box. For Georges Eustice, it is crucial to still have a share in the WTO amber box because of “certain shortcomings with WTO rules” because “the policies that would be more modern, more progressive, general risk management measures, at the moment, would probably be deemed under the WTO rules as amber box”. To conclude “In the longer term, as soon as we speak on our behalf again at the WTO, the WTO may have to revisit some of the these rules […] but this will not be a quick procedure”.

As though there was any doubt, with the exit from the European Union, the British have no intention of sacrificing their agriculture, quite the contrary. The Minister pointed out that, apart from lamb largely exported to France, their status as a net importer would result in higher producer prices if left to WTO ground rules. For Georges Eustice, it is indeed a question of not listening to economists “who will say that we could just stop farming and buy all our food cheap at world prices”. Taking the example of hormone-based bread and meat, he spoke of the importance of having domestic production in order to have affordable prices and standards in line with consumer expectations. And to finish by advocating pro-food sovereignty: “There are countries, in the Gulf for instance, that do not really have their own production at all or their own farming and they buy all their food at world prices, and as a general rule the amount of choice is lower and the prices are higher. That tends to be the outcome from countries that rely solely on world markets for their food supply”. As a result, European negotiators should expect the UK to try and recuperate as many import quotas as possible!

For the time being it is difficult to look into the future of British agricultural policy, the discussions are in their early stages and there are many stakes to untangle, all the more in the event of Scottish independence. However, we can presume that there will indeed be a British agricultural policy as was the case before their entry into the EEC in the early 1970s when, it should be remembered, they had a strong policy structured on counter-cyclical aid (deficiency payments) and public marketing agencies. Strange historical comeback, current discussions show that this type of support mechanism could once again become a reality!

Ultimately, the nature of the traditionally hostile British position vis-à-vis the CAP has taken another turn. Before being anti-CAP, the British were first and foremost anti-common policy. What lessons can be learned by the EU-27 and those responsible for European integration? In the first instance, the “northern Europe hostile to the CAP” group has lost its main political heavyweight. Secondly, if we are to relaunch European integration and stop the wave of Euroscepticism, the CAP must be put back on track by refusing decoupled aid and first and foremost giving the CAP countercyclical aids, as Momagri advises.

Frédéric Courleux, Director of studies of Agriculture Strategies

1 Les minutes de l’audition sont disponibles en suivant ce lien

http://data.parliament.uk/(…)/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/eu-energy-and-environment-(…).html