While Lactalis’ management of salmonella contamination feeds the chronicle, the report of Cash Investigation on the dairy sector broadcast last January 16 clearly shows the main ills of a whole section of French agriculture.

How to remain insensitive to the resentment expressed by breeders describing as slavery their relationship of dependence on their “client”? Can we talk about balanced trade relations when, on the one hand, a fully engaged farmer, both financially and humanly, faces, on the other, a global food giant with insolent external growth that freely impose his views on the price paid? If the relationship is not balanced, the price can not be fair and the added value inevitably leaves the agricultural link, with the risk of weakening the whole chain.

The bitterness of the producers

Misunderstanding is also great for producers who are members of a cooperative. In addition to criticizing the lack of transparency on business choices, cooperatives regularly find themselves having to welcome new producers whose processor has failed, which leads them to be globally less well placed in the most rewarding niches. Being able to generate capital to develop or buy brands is therefore a strong focus for them of a long-term strategy, which can become increasingly difficult to support breeders facing issues of survival in the very short term.

It is also necessary to speak of the bitterness felt by the producers who, as the 2015 milk quota approach, like Perette, came to dazzle the Chinese stomachs that are insatiable. The outlook is all the more wonderful as international prices were boosted by a scarcity built entirely by the New Zealand giant Fonterra controlling GlobalDairyTrade, the compass of international trade. The milk crisis passed by, and the leitmotif “invest-to-produce-more” turned into “getting into debt-to-earn-less”.

Finally, as illustrated by New Zealand, French farmers, for the most part, are aware of the limits of farm concentration; limits that it is for them and the indebtedness of the survivors of this market-or-break; and limits for the environment and animal welfare. At a time when we talk a lot about the circular economy, we should see in the persistence, in France, farms on a human scale, linking livestock and crops, a guarantee of environmental performance and not a survival outdated as it is often hears.

What solutions?

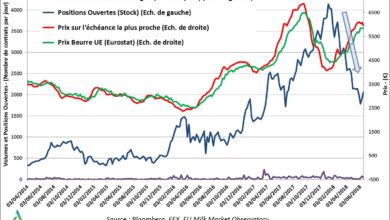

Solutions exist, but time is running out because the ingredients are already gathered to assist in the coming months to a strengthening of the milk crisis after the slight lull in 2017. The levers are at the same time at the community level but also at the level of the organizations agricultural professionals.

At Community level, it is first necessary to stop hoping in vain for the Common Agricultural Policy to make private risk management tools (income insurance, futures markets and mutual funds economic) effective, as experience shows. these instruments only operate with prices fluctuating regularly around the level of production costs. Then, it should be noted that the extreme volatility of prices is at the base of the infernal mechanism of extracting the added value of the link of production. The same goes for aid to farmers who end up more often with their suppliers and buyers than in their pockets.

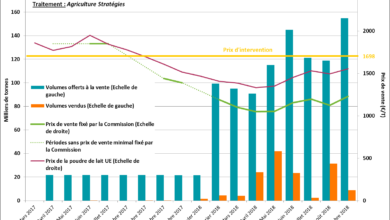

The European Union must therefore give itself the means for effective public action by combining variable income support with prices (counter-cyclical aids) and crisis management tools. Thus, at the bottom of the cycle, counter-cyclical aids can be a first-level safety net that is significantly more efficient than the fixed aids of the current CAP. And in addition, drawing inspiration from the voluntary aid program for the reduction of milk production, successfully tested at the end of 2016 on a European scale, the CAP must renew its approach to crisis management.

“The organization of the dairy industry is set to evolve”

On the basis of this base of regulation essential to limit the effects of imperfections of the market, the organization of the dairy chain is also brought to evolve to exceed the current report of a sharing of the unbalanced added value between two links in mutual dependence one of which, the processors, is clearly more powerful than the other, the producers. The United States, like Canada, has solved this problem by putting in place a collective bargaining at the level of 3 or 4 states where is defined each month the price of milk according to mathematical formulas integrating the evolution of the markets of the products dairy. Equalization is even established between dairies: the best positioned contributors for those who produce products with low added value. A study that we conduct shows that, transposed to France, this device would have allowed French farmers to have an average price of 13% higher over the last 10 years.

A transposition of this type of device is possible in Europe because our country is not the only one to be affected by this problem. Changing the structuring of the sector, a solution put forward by President Macron in his Rungis speech, is also a means to achieve a similar result. It would then be necessary to leave the logic of contractualization advocated since 2010 to envisage a real massification of the offer.

In a sufficiently large territory, an actor, such as a well-established cooperative, would group together the entire offer and negotiate with each processor a milk purchase price taking into account the valuation made.

These actors, 5 to 10 at the national level, would thus be responsible for the management of volumes produced, in time and space. In this way, the price of milk would be much less sensitive to fluctuations in the prices of industrial products on the international markets.

This better organization relies mainly on the initiative of the farmers themselves, individually, and collectively through their cooperatives, their producer organizations and their unions. The public authorities must accompany this development and improve the transparency of the markets for processed products, particularly opaque in France, where quotations are made by the manufacturers themselves.

“Produce at below cost of production”

On these new foundations, issues related to the environment and animal welfare can be effectively addressed. This is not the case today where farmers are subject to contradictory injunctions: on the one hand, producing at prices that are often lower than production costs to ensure the competitiveness of the agri-food industry; and on the other, to integrate constraints on their mode of production to limit their environmental impacts. By making pastoralists more secure, a new pact will emerge in which tools aim8ed at limiting the concentration of livestock farming, improving their fodder autonomy or fully exploiting the carbon capture potential in the soil will become acceptable.

Frédéric Courleux, Director of studies of Agriculture Strategies

This article was also published in Paysan Breton on the 01/24/2018, and is available at the following link :

http://www.paysan-breton.fr/2018/01/pour-en-finir-avec-la-crise-du-lait/