Australia and New Zealand are major exporters of ruminant animal products (sheepmeat and beef, dairy products). But the low growth potential of their production, their proximity to the Asian markets and the weakness of current trade with the European Union leave a doubt about the interest that the Pacific countries would have in a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU. These negotiations, officially launched on the 18th of June, rather seem to be coming from the Commission, a surprising initiative given the uncertainty surrounding Brexit and the current distribution of tariff quotas.

Being major players in the international markets for animal products (meat and dairy products), Australia and New Zealand have undeniable advantages for these productions as shown by a study conducted by ABCIS for the French Ministry of Agriculture. Articulated around a synthesis and fact sheets specific to the different markets of the two countries, this study gives an overview of the oceanic sheep and cattle sectors, with particular attention given to current trade flows with the old continent. The wealth of information gathered in this way provides an overview of the economic situation of these sectors, as negotiations for a free trade agreement between the EU and Oceania have just begun.

Strengths and strong limits

If New Zealand has pedoclimatic conditions that are quite favorable to grass growth and therefore to ruminants, this is not the case in Australia, where the size of its territory is one of its main assets. Both islands have therefore largely developed animal production through grazing and are highly specialized. New Zealand has been producing 35% more beef over the last 30 years and doubled its milk production over the last 20 years, to the detriment of its sheep industry (-31% production in 30 years). Similarly, Australia has seen its beef production increase by 61% in 30 years, while sheep and dairy productions are relatively stable.

This dynamic should nonetheless fade for opposite reasons: on the one hand, the density of New Zealand livestock is very high, generating significant concerns about the evolution of ecosystems ; and on the other hand the recurrence of droughts in Australia puts a strain on livestock farming in most parts of the country. Therefore, the growth potential of production is limited.

If Oceanian Island farms are the champions of international markets, it seems that this search for competitiveness in a context of growth has also damaged the sectors and producers.

In Australia, dairy processors have now largely gone under foreign flag since the bankruptcy of the leading Murray Goulburn dairy co-operative whose assets were bought out by Saputo, a Canadian company. Thus, 80% of Australian dairy processing is in the hands of 4 foreign companies (Saputo: Canada, Fonterra: New Zealand, Kirin: China and Lactalis: France). In New Zealand, the situation is not the same, but next to the local juggernaut Fonterra, several private operators (mainly Asian) have gained a foothold in the dairy sector and directly deal today with 12% of collected milk.

The high debt of New Zealand livestock producers has also resulted in the influx of foreign capital into the production level. For example, Theland Farm Group, affiliated with Alibaba, has established itself among the Kiwis despite government’s action to reduce this phenomenon. Similarly in Australia the purchase of the largest farm in the country which was making headlines at the time (Kidman farm of 11 million hectares) could only be done with a minority presence of Chinese investors.

Export flows redirected to Asia

The two Oceanian countries are currently exporting to the EU via zero or low duty tariff quotas negotiated largely as a result of the UK’s entry into the EU and granted for historical trade reasons between Commonwealth countries. These quotas, which all account for a small share of Oceanian exports (less than 10% for each product), have not been saturated in recent years: export opportunities to Europe are not fully used today.

Sheepmeat is mainly exported from New Zealand to the United Kingdom (duty-free quotas), and concentrates on cuts rather than carcasses. In the same way, these countries export to the EU “high quality” beef (a 20% duty-free quota) representing less than 3% of their exported volumes. Similarly on dairy products, the quotas (customs duties of 40 to 50%) are not filled.

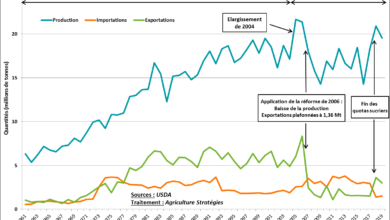

If the EU is rather a declining destination for Oceania, these two countries continue to increase their exports to Asia. Both Australia and New Zealand are involved in free trade agreements with 15 Asian countries, and have recently signed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which strengthens their ties with these markets. China, with its rapid growth, now absorbs as many sheepmeat exports as the EU, as can be seen in Figure 1. Similarly, the top destination for beef and dairy exports is Asia. A trend that should be confirmed in the future as the Asian markets are growing and Oceanian production capacity are coming to saturation.

Why is an EU-Oceania agreement being negotiated?

Faced with these findings, one can only wonder about the interest that Pacific countries would have in initiating the negotiations for an FTA with the EU in order to increase their exports of animal products. Their proximity and their complementarity with Asia make the most populated continent in the world their natural market.

Moreover, the uncertainties surrounding Brexit with regard to the allocation of tariff quotas between the EU and the United Kingdom, which is the main gateway for Oceanian exports, argue on the contrary not to overly complicate an already difficult situation. This question worries European producers: the FNO in its activity report calls for a distribution of quotas on historical bases while the Copa-Cogeca has qualified as “unwelcome” the negotiations of access to the EUmarket even though the uncertainty on the Brexit hangs.

The opening of this new negotiation seems to corroborate the hypothesis of a rush forward on the part of a DG Trade who seems to have difficulties in establishing the diagnosis of the crisis of multilateralism and prefers to save appearances by being pro -active on bilateralism.

While sheep and especially beef, which are the best able to use European grasslands and their carbon stocks, are already in difficulty because of the commercial pressure within the sectors, we can consider that this negotiation is useless. Whether it was among European producers or their Pacific counterparts if it achieved anything other than the status quo.