OECD just dedicated an in-depth study to agricultural policies in India. This study was all the more expected as India, at the head of G33, disputes the WTO rules regarding agricultural policies and aims at doubling agricultural income before 2022. First world exporter of rice, first producer of milk, India is also a country where another 1 inhabitant on 6 suffers from malnutrition. The food shutter of the Indian agricultural policy is central: approximately 30 % of national production of grains are bought back and stored by various public services to be resold to the most deprived categories of the population at low prices. However, OECD recommendations do not seem as relevant as the whole report. Structural adjustment, so drift from the land, end of public storage, converting to monetary transfers for undernourished people and direct payments for producers: the OECD medicine and its faith in the smooth running of markets seem irremovable, what makes it completely irrelevant in face of the Indian complicated situation.

OECD just published Agricultural Policies in India1, a first time report closely interested in various agricultural and food policies at work in India, rather known to go against the WTO rules and thus to OECD doctrine, in particular on public storage. This report was all the more expected since the Indian government of Prime Minister Modi showed its will to double agricultural incomes before 2022, even if the report remains rather evasive on this point.

A report rich in teachings …

The report proposes a history of the Indian agricultural policies beginning only from 1960s. As other branches of industry of the country, Indian agriculture went through important transformations for the last decades. The green revolution in the field of cereal opens this process up from the end of 1960s, followed in the 1970s by the white revolution in the dairy sector and the genetic revolution of the 2000s which will benefit the cotton sector in particular. From now on, the changes in new middle class consumption put forward as main explanatory factor for the changes in production with a diversification towards protein crops, fruits and vegetables but also meat-based products. Nevertheless this historic part leaves the food crisis of 2007-08 and its political repercussions untold which at least is surprising.

The structural analysis of Indian agriculture paints a portrait of an major sector of the country economy: 17 % of the GDP and 47 % of working population. The Indian agriculture is made at 85 % of small exploitations, less than 2ha, that still farm 45 % of cultivated surfaces. With mainly crop-livestock farming, only 4% of total exploitations exceed 4ha. There are still lots of isolated rural areas with heavy structural problems: sector organization, access to new technologies or functioning cold chain. Thus the Indian agriculture is characterized by a rather low productivity, which does not prevent the country from being the world first producer of milk, the second for wheat, rice, cotton, sugar, tea, fruits and vegetables. In spite of important limitations on exports, it is also the world first exporter of rice, beef and spices.

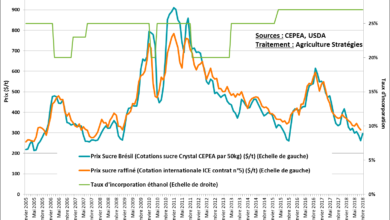

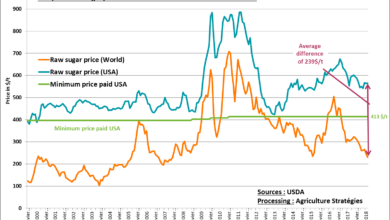

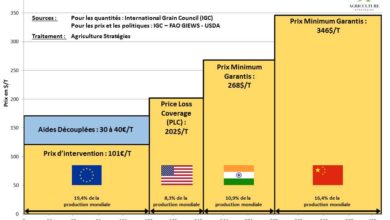

India also distinguishes itself with massive public food purchases: 30 % of national production of wheat and rice are collected by the State through the TPDS (Targeted Public Distribution System). These commodities are bought at a minimum price support to the producers (MPS). On wheat and rice for example, it practically tripled since 2006. According to Igc, it reached 230 $/ton for wheat in 2017. In addition there is a control of exports and imports, mainly thanks to customs duties. Most of domestic productions are protected by high customs duties. Conversely, products necessary to industries or household consumption such as vegetable oil and proteins are submitted to no customs duty. Other products exports are forbidden such as legumes seeds, subjected to quotas or require a license. Public purchases representing about 30 % of the national production, the report indicates that prices paid to producers align themselves with the MPS even if that can be discussed. These wide public purchases campaigns are articulation of a same policy on both agriculture and nutrition.

While the country matters for 18 % of the world population, 191 million Indians suffered from malnutrition over the period 2014-2016. One might as well say that the quarter of undernourished people in the world live in India. These figures should not be neglected, even if they seem to get better: in the 1990s, 1 Indian on 4 went hungry, against 1 on 6 in 2014. Even if the report does not also go far to its evaluation, this improvement would be partially attributable to the TPDS program:

Approximately two thirds of the Indian population are relying on TPDS or an equivalent program which allows the most deprived households to buy staples, wheat and rice mainly, at a low price: CIP (Central Issue Price) which was not revalued since 2013. Since 2007 these programs helped a maximum of 75 % of households in rural areas and 50 % in urban area. The numerous exports limitations, pointed after the 2007-08 crisis, would have maintained internal low prices and especially protected the most vulnerable populations from hazardous international prices.

A particular attention is carried in the report with climatic stakes upon India. Arable land undergoes a very strong erosion pressure. About water, the report moves forward the prospect of a request increasing by 32 % on the 2050 horizon even if the country already knows regular shortages. That’s why an important part of agricultural budgets is already dedicated to irrigation. Water management in general will be a key factor in the next decades: multiple pollutions in which the farming sector participates, intense alternation of periods of drought and destructive floods.

… with highly surprising conclusions

The ESP indicator (estimation of support to producer) is the key indicator in studies led by the OECD and allows a comparative approach to agricultural policies of various countries thanks to the same methodology of evaluation. So a high ESP will be synonymic of an agricultural policy which, in the eyes of the OECD doctrine, will be considered as “a burden which presses on consumers, producers and taxpayers”. The report also proposes calculation of the ESC (estimation of support to consumer) and EST (estimation of total support), EST being sum of ESP and ESC.

At first sight, Indian ESP seems rather surprising considering previously presented ambitious measures. For 2014-2016 period, OECD announces a negative ESP equivalent to -6,2 % of the agricultural receipts. The report presents two main ESP components: direct support (from taxpayer to producer) would amount about 7 % of value of the agricultural receipts mainly as subsidies to inputs; a price support (from consumer to producer) of -13 %, like as if producers were supporting the consumers by globally lower market prices than the international prices ones. This seems hard to believe as far as public storage purchase prices won’t stop increasing, in particular for cereal and protein crops. Unfortunately reference prices are not available in the report which does not allow understanding this visible paradox. A breakdown by products type would maybe have helped us a little more. At this stage, we shall consider that important fruits and vegetables productions in India, international quotations of which are delicate to establish, make negative this ESP component. At the same time, cereals and protein crops take advantage of market support all the more positive that the internal prices increase while international prices decrease.

Support to consumers, represented by ESC, was insignificant in the 2000s. Today it reaches an average 25 % of value of products, on all farm produces, which is far from being unimportant. It translates partially financial amounts associated to the difference between purchase prices to producer (MPS) and prices of resale (CIP) but also describes the valuable difference between international market prices and the very split up and nevertheless enormous internal market ones. In these conditions, EST indicator (estimation of total support) is difficult to interpretable because its level hides very important transfers although very different ones between categories of products. The usual ESP, ESC, EST group can barely represent the Indian reality and could not get loose from a precise comment.

…and blind recommendations

It is at the same time a rich and paradoxical report, and it presents a gap between its demonstrations and the recommendations which are made. Indeed, the complexity of context and studied institutions fades very fast to give way to orientations with no signs of vigilance with regard to possible “market failures”, an expression that does not appear once.

So, OECD advises India to reduce or better to stop its public storage programs to let emerge private actors who, by definition, will do better. It is at the same tine granted that the most fragile producers “could be subject to exploitation by the traders and the retailers “. Also MPS is logically pointed and should be lowered to get closer to international courses, losing all their interest by the way. To replace it, OECD pleads for direct producers support measures, but strangely, does not mention initiatives such as price deficiency payments, a countercyclical aid plan currently on approval in Madhya Pradesh.

On food safety, major problem for the Indian governments, it is handled here in an unacceptable way. OECD suggests that India gets rid of public distributions programs such as TPDS to monetary transfers to the poorest which would be free to buy their food themselves (cash transfers). However, the authors of the report took time to describe inconveniences of this approach; nevertheless inconveniences were presented as “minor” : “the poorest would not be protected anymore from the sharp rise in prices, nor from volatility of world courses. […] With the prices increase, the same support would probably not be enough to buy the same food quantity and it would not be possible anymore to ensure a stock big enough for domestic consumption. […] Also, payments could be also diverted from their first vocation, nutrition”, leaving in particular the infantile population in an all the bigger distress. These limits, well known, do not however prevent the authors from keeping professing monetary transfers! The Indians do not seem fooled at all because main reactions to the OECD report concerned this point. Returns on experiments led in certain Indian States are so told: problems of payment times, absence of payments, incapacity to find on the market the quantity of necessary food with the amount granted, etc.

Finally, OECD suggests increasing size of exploitations to increase productivity. Surfaces being limited, this enlargement would thus be translated by an important decrease in number of farmers. And while the report reminds us that Indian metropolises are already under stress, a question emerges: What are these ex-farmers going to do and where are they going to live? We indeed refer to about 600 million Indians who currently directly depend on agriculture. There also, we can wonder why producers’ cooperatives and in a general way group farming stay untold. It is all the more harmful as initiatives are accompanied in this direction as the economist Bina Agarwal shows.

So, it is a report rich in contents and made of an important work from OECD, since it is the first complete report on mechanisms at work in India. Nevertheless, the OECD method shows also its limits in front of complexity characterizing the country: how to propose such grotesque recipes while dealing with the future and safety of hundreds of millions of people in a country so decentralized and multiple? Exposed without specifically bound to the context argumentation, recommendations in Indian agricultural and food policies evolution are not accompanied by a characterization of periods of transition which way allow them to happen. To resume the recent analysis of economist Dany Rodrik, specialist of compared development, we can only see here the expression of dogmatism, a diversion of the economics where we try to transpose some principles without taking into account the diversity of the institutional adjustments appropriate to every country.

Océane Lachaussée

2 https://www.lemonde.fr/asie-pacifique/article/2016/02/29/l-inde-fait-du-developpement-agricole-une-priorite_4873543_3216.html

3 https://www.igc.int/_security/getfile.aspx?f=np\4xx\47x\472\GMR472India.pdf

4 Le CIP, maintenu à de faibles niveaux, est le prix d’achat pour les bénéficiaires des programmes d’aides alimentaires

5 OCDE, Agricultural Policies in India, juillet 2008, page 200

6 OECD (2017c), « Producer and Consumer Estimates », OECD Agricutlure Statistics Database, est la seule référence OCDE de la page 58 sans lien vers une base de données

7 OCDE, Agricultural Policies in India, juillet 2008, page 267

8 http://www.financialexpress.com/budget/budget-2018-fix-farmers-woes-by-going-the-telangana-way-heres-how/1033854

9 https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/agri-business/cash-transfers-more-effective-than-pds-says-icrier-oecd-report/article24382172.ece

10 Bina Agarwal (2018). “Can Group Farms Outperform Individual Family Farms? Empirical Insights from India”, World Development, 108: 57-73

11 Dani Rodrik, 2018, Le néolibéralisme ou l’économie dévoyée, l’Economie politique n°78, Alternatives Economiques.