Access the full study Download the summary’s PDF

Agriculture Strategies publishes a study of which we have reproduced the summary below. This study focused on US dairy policy, and in particular the federal milk marketing boards. Milk characteristics prevent spontaneous price formation and induce economic dependence between the links of production and processing. By transposing US price formulas, the price of milk in France would have been 13% higher over the last 10 years. The next reform of the CAP should be an opportunity for the public authorities to support a reorganization of French dairy farmers.

Improving the mechanisms for value sharing within the value chains and strengthening the organization of producers are two topics at the heart of agricultural policy debates at both the French and European level. In France, the dairy sector has been particularly concerned by these issues since the end of milk quotas, and the “contractualisation” put in place since 2010 does not seem to have given sufficient answers.

Also very connected to international trade, the American dairy sector was less impacted by the crisis of global overproduction that began in 2014: the milk price differential was clearly to the advantage of US producers and production and exports have continued to grow.

Since the 1930s, milk has been marketed in the United States through Federal Milk Marketing Orders, which are made up of two-thirds of producers in a given region. There are currently 10 federal marketing boards and Californian producers have just voted to create the 11th. In this way, 80% of US production is affected by this regulatory measure.

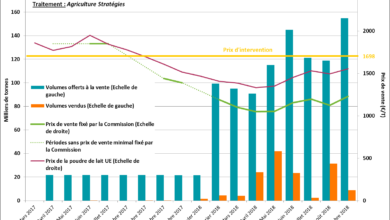

The main function of the boards is to achieve fair value sharing between producers and processors on the basis of price formulas. Each month is thus defined an identical minimum price for all producers. It is based on the evolution of the markets for processed dairy products. The price formulas are modifiable but they are now identical for each of the 10 offices and stable for at least 10 years. The operation of the system is based on a significant transparency of the actors of the transformation who must notify the volumes and the selling prices of the finished products.

If the minimum monthly price is the same for all producers in the same office, the price at which the processors buy supplies differs according to the type of valuation they make. Equalization is thus directly effected between companies positioned in high-value-added segments that give up part of the value thus created to companies with less good “mix-products”. This is the equivalent of 10 to 15% of the turnover of milk producers who transit through the offices to operate this equalization.

The policy of sharing the value of milk at work in the United States bears witness to American pragmatism in economic matters. The perishability of the milk induces a situation of economic dependence between producer and processor: we will never see 3 tankers follow each other in the country roads to go, every 2 or 3 days, to solicit the producers and offer them a different price. Thus, since the spontaneous formation of a market price is not possible, the Americans have chosen to institutionalize the formation of milk prices while leaving markets open for other dairy products.

Using French data on prices and volumes of processed products, we have transposed the FMMO price formulas to the French dairy farm. Comparing with the price received by French producers over the period 2007-2016, the transposition of the US policy of sharing value added would have generated – all other things being equal – a rise in the price of milk of 13% or € 43 / 1000 liters. This result is explained in particular by the significant weight of cheese in the FMMO price formulas.

In addition to the United States, Canada also has a collective marketing system that allows equalization between different valuations. Giant cooperatives in the Netherlands, Denmark and New Zealand have a quasi-monopoly situation at the national level that allows them to carry out equalization internally. Faced with these competitors, French producers suffer from a competitive organizational disadvantage: the cooperatives collect about 55% and transform 45% of the French milk production.

The level of valuation of industrial products seems to have an excessive weight in the setting of prices in France whose level would be largely determined by the product mix of the main cooperatives. The average valuation of the latter is less good because they have had to recover volumes during the restructuring of the transformation in order to avoid collection stops in certain territories, where private companies have been able to develop valuation strategies centered on the most profitable consumer segments.

Given the tensions regularly observed in the industry and sometimes archaic commercial practices – unilateral termination of agreements, pricing after removal, etc. – it seems necessary to reorganize producers to get them out of excessive economic dependence. Failing this, the decline of the French dairy sector, which is starting to manifest itself in the non-recovery of output volumes, could lead to a drop in production of at least 30% by 2030.

The “contractualisation” initiated in France to anticipate the end of milk quotas has not produced the expected results. A contract alone can not rebalance a business relationship. With the end of the quotas approaching, the formation of sufficiently strong Producer Organizations (POs) has not been accompanied by the public authorities (delay of the decree on the recognition of POs, no use of the 2nd pillar of the CAP ). And dairy cooperatives have obviously wanted to stay on the fringe of “contracting”.

The extension of the logic of “sectoral interventions” announced for the post-2020 CAP could accelerate the reorganization of the dairy sector in France. Already at work for the fruit and vegetable sector, “sectoral interventions” can encourage the formation and financing of POs (usually cooperatives) for their R & D, risk prevention and, above all, planning activities. production and adjustment of production on demand. Conditionalizing aid coupled with participation in a PO would also be an attractive incentive.

French dairy cooperatives will therefore face a crucial choice. Either they decide to take the bull by the horns and organize, by homogeneous territorial entity, their rapprochement with the existing POs in order to gradually integrate the producers of the latter as co-operators. Either POs will be formed within the cooperatives and these POs will be organized into a Producer Organization Association (PDO) at the basin scale and the cooperatives will then specialize in their transformation activities, as in the United States.

It would then come out of the paradoxical situation of the French dairy farm where, on the one hand, a half of producers is well organized in cooperatives whose valuations of milk are average, and on the other hand, half of barely organized producers. in POs with no real bargaining power over highly placed processors in higher value-added segments.

It is therefore crucial that dairy producers get mobilized now to anticipate the next CAP reform and work towards the reorganization of production in order to be at the heart of the management of volume management and the sharing of added value within of the sector.