The abolition of the European sugar quota regime in 2017 did not have the expected results. The prospect of increasing European production to develop exports quickly turned into a drop in sugar prices and tensions in the governance of the sector, particularly in France. Heavy industry par excellence considering the transformation process, where the perishability and the heavy nature of the raw material explain the strong dependence between the links of the production and the first transformation, this sector also does not have important margins of maneuver to build a strategy of upmarket and “decommoditization”.

In these conditions, the exposure to the volatility of international markets, where the surpluses of the main producers are mainly exchanged, can undermine the entire sector because of a lack of strong public policy. In order to envisage a new regulatory framework for European sugar production, we propose a series of articles to study the different sugar policies of the main sugar producers. We will focus on Brazil, India, Thailand, China, the United States and Russia, which together with the European Union account for nearly two-thirds of world production (see Figure below). ). This panorama will allow us to conclude this series by constructing different scenarios of evolution of the European sugar policy.

With around 10 million tonnes, Thailand was the 4th largest producer of sugar in 2016, accounting for 5.8% of world production. This production comes from sugar cane, whose production is fairly evenly distributed between the provinces of North and East of Thailand (Figure 1). The sector has more than 300,000 producers, grouped into 33 associations of planters who deliver 55 processing plants1. Commercial relations between planters and factories are highly regulated: the sharing of value is administered by the State.

Figure 1: Distribution of sugar cane production in Thailand

The Thai sugar sector developed gradually from the 1980s. From marginal production in the early 1960s (less than 150,000 tonnes of sugar per year), it grew to an average of 10 millions of tonnes at the beginning of the 2010s. This transition is due in particular to a voluntarist policy that has allowed it to flourish.

In 1984, the Cane and Sugar Act came into force following a crisis of overproduction that affected domestic sugar prices. This legislation introduced a minimum internal price, a triple-quota system that is quite similar to the European regime of the time and a control of the distribution of value between planters and sugar factories2.

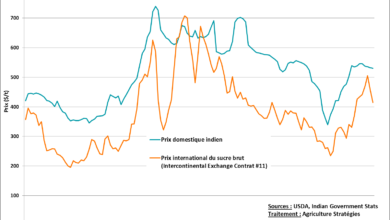

The quota sugar A is sold on the national market at the price fixed by the government, it represents 2.6 million tons. B quotas, which cover 800,000 tonnes of raw sugar for export, are regulated by the Thailand Cane and Sugar Corporation (TCSC). Finally, if these two tranches are exceeded, the processors export the surpluses without quantity constraints. The cane price for producers is based on the valuation of sugar factories: after taking into account processing costs, the value is divided between producers (70%) and sugar factories (30%)3. Figure 2 shows the domestic minimum price, the main Thai export quotation, and the international benchmark.

Figure 2: Sugar prices in Thailand, out of the territory and on the international market

In addition to value sharing, payment on delivery of the cane is also taxed. In case of overpayment compared to the actual valuation established at the end of the campaign, it is the State that reimburses the processors. Associations and federations of producer associations act as intermediaries between producers and processors.

The triple-quota system is funded in part through the levying of a tax on sugar sold on the domestic market and a 7% VAT, paid to the “Cane and Sugar Fund”, which in turn provides support to investment for processors and producers. In addition, this policy is accompanied by border protection, with sugar being taxed at $103/t, with the exception of ASEAN4 members who have preferential tariffs for access to the Thai market5.

The calling into question

Victim of its success, the Thai sugar policy has been questioned. The significant development of its production has led Thailand to become a major exporter and thus to become more sensitive to fluctuations in international markets. In 2015, the authorities announced a “National Energy Plan for Thailand” whose objective is to develop alternative markets for cane through the production of ethanol with the objective that 25% of fuels come from biofuels by 2036.

Above all, in 2016, Brazil’s WTO attack on Thailand’s sugar policy pushed for far-reaching reform, not all of which has yet been finalized.

From the 2018-2019 season, the price of sugar on the domestic market is no longer fixed by the government, the quota system is entirely abolished and taxes abound on the public fund as well6. Processors still have the obligation to build a safety reserve of 250,000 tonnes per month in order to protect the domestic market from possible shortages. According to USDA forecasts, these developments should lead to a 25% decrease in cane prices compared to their 2016-2017 level.

Figure 3: Evolution of brown sugar production in Thailand (Source: Cristalco)

As shown in Figure 3, Thai production continued to increase, reaching a record in 2017 with nearly 15 million tonnes, which allowed it to export 10 million tonnes or 16% of international trade. This rise is presented as the first factor explaining the fall in international prices with the end of European quotas. Four million tonnes of global production of more than 170 million would have been enough to turn the market around, further evidence of the extreme volatility of international markets where a small gap between production and processing results in significant price changes.

Despite the reform undertaken and the fall in prices that it has generated, production in 2018-2019 is expected to decrease slightly compared to 2017-2018, well above the previous years. Cane being a perennial crop and limited alternatives for producers, this is not surprising: in agriculture, as in all heavy industries, the price adjustment is above all a view of the mind. According to the USDA, production is expected to increase further in the coming years as two new processing plants and associated acreage are brought into production.

In the end, there is more to wait for the decisions of the Thai government which announced the development of oil palm plantations7. The government’s objective is to increase the area of palm trees by two and a half times, in particular to meet the objective of increasing the share of biofuels in fuels and in particular biodiesel8.

1 https://www.bonsucro.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Thai-White-Paper-FINAL-LowRes.docx.pdf

2 https://sugaralliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Meriot-Thai-Subsidy-062015.pdf

3 https://www.krungsri.com/bank/getmedia/64a1559a-2938-4f48-b5af-c601e52f660c/IO_Sugar_2018_EN.aspx

4 The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is a regional organization for economic, political and cultural cooperation that brings together 10 Southeast Asian countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Brunei, Vietnam , Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia).

5 https://sugaralliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Meriot-Thai-Subsidy-062015.pdf

6 https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/dispu_e/cases_e/ds507_e.htm

7 https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Biofuels%20Annual_Bangkok_Thailand_6-23-2017.pdf

8 https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Biofuels%20Annual_Bangkok_Thailand_6-23-2017.pdf